Planarian, or Flatworm

I ran across an article about the work of psychologist James V McConnell, who, in 1960, seemed to have demonstrated that memory was stored not just in the brain, but in the whole body.

McConnell trained planaria (singular: planarian), a goofy-looking, one-inch worm that has a brain. These flatworms, as they’re also called, curl their tail when given an electrical shock. Who wouldn’t?

When a planarian is repeatedly warned by a bright flash of light that a shock is coming, it curls its tail when the light comes on, even before the shock, an anticipatory association psychologists call “classical conditioning.” For the trained planarian, the flash of light means, “OMG! A shock is coming!” (Perhaps not in so many words, of course).

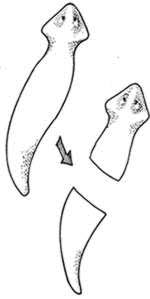

The head and tail each regenerate a complete new worm

Any animal and even some plants can be taught to remember something by using classical conditioning. Ivan Pavlov won a Nobel Prize in 1904 for work that used this kind of training. What makes planaria fun to teach is that they also regenerate. If you cut one in half, the head grows a new tail, and the tail grows a new head.

McConnell claimed that in his experiments, when he retested trained planaria which had been cut in half and regenerated, the “new” worms (half-new, really) still remembered what they had learned. Maybe that’s not surprising for the head, where the worm’s little brain is located, but the tail? How could the tail remember what its decapitated head used to know?

The study raised questions about where memory is stored. We thought it was the brain. Is it really all over the body? Does my elbow remember reading Sartre’s Being and Nothingness? Does my kneecap know my bank password?

Upping the ante, McConnell ground up trained planaria and fed them to untrained planaria. The cannibals showed memory of the original training. That seemed to clinch it. Memories are stored in the whole body, not just in the brain as we had thought.

Humans don’t regenerate, so our memories may be stored only in the brain, although my golf swing is definitely stored somewhere else. It could be that memory is distributed throughout the body in a flatworm but not in other animals. Scientists should try the experiment on starfish and other animals that can regenerate.

As it turned out, other laboratories could not repeat McConnell’s findings and his results (and he) were soon discredited and the whole sensational episode became a footnote in intro psychology textbooks. McConnell died in 1990.

Recently, however, the topic has been revived. Biologist Michael Levin at Tufts University has convincingly replicated McConnell’s original finding that regenerated planaria do remember the training their original selves received.

(Shomrat & Levin, 2013. http://jeb.biologists.org/content/early/2013/06/27/jeb.087809. Secondary source: www.theverge.com/2015/3/18/8225321/memory-research-flatworm-cannibalism-james-mcconnell-michael-levin).

Planarian size

Of course there is no perfect experiment, and this finding could yet be overturned, but assuming it’s good, how can it be explained? There is no biological explanation of how memory is stored, either in the brain, or anywhere else in the body. And don’t even start asking about recall. That’s way over the horizon. Science just does not know much about memory.

I think the fundamental question is wrongly formulated. We don’t know what we’re talking about and that’s why we don’t have answers. What is “a memory?” Nobody can say. It’s a badly defined idea, a blend of subjective intuition and biological hypothesis.

There’s a psi-fi opportunity here. Nothing could be more “psychological” than memory. Whatever it is, it lies at the core of the human mind. Add to that the fact that there’s no scientific explanation for it, or even a proper definition, and you’ve got fertile ground for a psi-fi story.

Many good psi-fi stories have been done on memory, on topics from amnesia (always a fave) to selective erasure, to learning pills, to memory transfer from person to person, or even across species. But nobody has really focused down in on this idea of what the “unit” of memory is, how it’s defined, and where it’s stored in the body. Maybe I’ll do it.