Written in 1974 when the Soviet Union controlled Poland, this tale of “the future” (2039) can be read as a criticism of authoritarian systems and their unceasing domestic propaganda that tells citizens how good their life is, when it is starkly apparent that they are living in misery. If you read it that way, this novella stands with Animal Farm as a sly satire.

Written in 1974 when the Soviet Union controlled Poland, this tale of “the future” (2039) can be read as a criticism of authoritarian systems and their unceasing domestic propaganda that tells citizens how good their life is, when it is starkly apparent that they are living in misery. If you read it that way, this novella stands with Animal Farm as a sly satire.

The setup is that a Profesor Tichy attends a conference of “Futurologists” in Costa Rica. Alvin Toffler’s international bestseller, Future Shock! had come out in 1970, identifying social paralysis induced by rapid technological change. In 1968, Paul Ehrlich had predicted in The Population Bomb, worldwide starvation and societal upheaval due to overpopulation. Also at about that time, a revolution in psychiatry was underway as new tranquilizers, anti-depressants, and other anti-psychotic drugs reached wide usage. Lem put all these ideas together in a uniquely Kafkaesque way to make a mordantly humorous tale of a dystopian future.

The Congress, in the San Juan Hilton, is a head-spinning affair fueled by drugs even in the water supply, it turns out. After drinking some, Tichy recalls an article in Science Today about new psychotropic agents, the “so-called benignimizers (the N,N-dimethylpeptocryptomides), which induce states of undirected joy and beatitude…Hedonidol, Euphoril, Inebrium, Felicitine… I found myself kneeling over a suitcase, frantically pulling things out to find some article of value I could give to the needy…I was torn in two. I felt such a sudden surge of the categorical imperative, that I wouldn’t have touched a fly.”(pp. 16-17). That early passage is prelude: eruditely funny yet farcical.

After a cryogenic episode, Tichy finds himself living in the future and trying to get a grip on its strange language, ways, and values. The world population is 30 billion, so many people crammed into such tiny spaces that everyone takes psychoactive drugs to believe they live a good life, not the near-death squalor they actually occupy.

As before, the humor is deadpan and delightful. “There was another administrator… who… trafficked in white slaves – they called him “le computainer,” since he’d been built on commission by the French.” (p. 86). However, the shtik becomes wearisome. At a party, a “leostat,” a hunter of artificial lions, tells Tichy about “black natives [in Africa] who changed their race by taking caucasium. However—I thought—is it right to solve chemically such serious, deep-rooted social problems as prejudice and discrimination?” (p. 97).

On and on it goes with clever neologisms, but even with hats off to the translator, that’s all there is. Unlike P.K. Dick’s 1969 novel, Ubik, which this one recalls, The Futurological Congress is a long exercise in Lem’s cleverness, which is considerable, but I found my interest flagging. It’s a one-trick pony. Finally, our hero discovers the evil oligarchs who run the whole drug-managed population and he learns of “dehallucinides,” which create the illusion that there is no illusion, designed for suspicious people like him. I can’t remember how the story ends but it doesn’t matter.

Any longer and the book would be tedious, but at 149 pages it is almost the right size for an enjoyable and thought-provoking linguistic joke and social commentary and a pure exercise of the psi-fi theme: psychological fiction in a technological world.

The Futurological Congress was made into a wonderful 2013 movie called The Congress with Robin Wright, Harvey Keitel and Jon Hamm. The movie doesn’t have a high rating but I loved it for its sheer creativity, both director Folman’s and Lem’s.

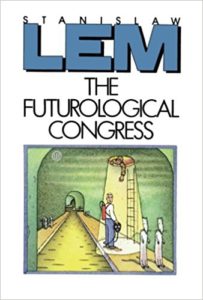

Lem, Stanislaw (1974/1985). The Futurological Congress: From the Memoirs of Ijon Tichy. Michael Kandel, trans. New York: Harvest, 149 pp.